- Start date

- Duration

- Format

- Language

- 1 Dec 2025

- 3 days

- Class

- English

Doing a comprehensive strategic exercise as the executive leadership team of a hospital to test and strengthen managerial and organizational skills.

In a cartoon by Italian comic artist Jacovitti, a sign in the usual fantastic saloon asks customers “not to shoot the pianist from 3 PM to 10 PM.” Since 2018, similar signs have appeared in Italian public healthcare facilities: “Please do not hit the staff,” “Remember that insulting or assaulting the facility's staff is a crime.” What are these signs telling us? Do they imply that among the various forms of interaction with healthcare professionals, there is one that expresses violence? What do we know about the effectiveness of these actions?

Just as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so too is aggression towards healthcare workers perceived only by those who organize to observe it. Data from the 2023 National Observatory on the Safety of Healthcare and Social Workers depict a scenario where the most episodes of violence are recorded in contexts that have addressed the issue, with a North-South gradient suggesting it is a typically Northern phenomenon. In reality, Regions like Veneto, Lombardy, and Emilia-Romagna are simply where sensitivity on the subject is spreading more quickly.

Official estimates are quite conservative (15,000 reported cases), while some professional associations claim that 95% of episodes go unreported and that the phenomenon affects an average of one nurse in three annually, accounting for about 130,000 cases per year. Other studies estimate that nine out of ten nurses are involved (in which case the number of cases would approach 400,000).

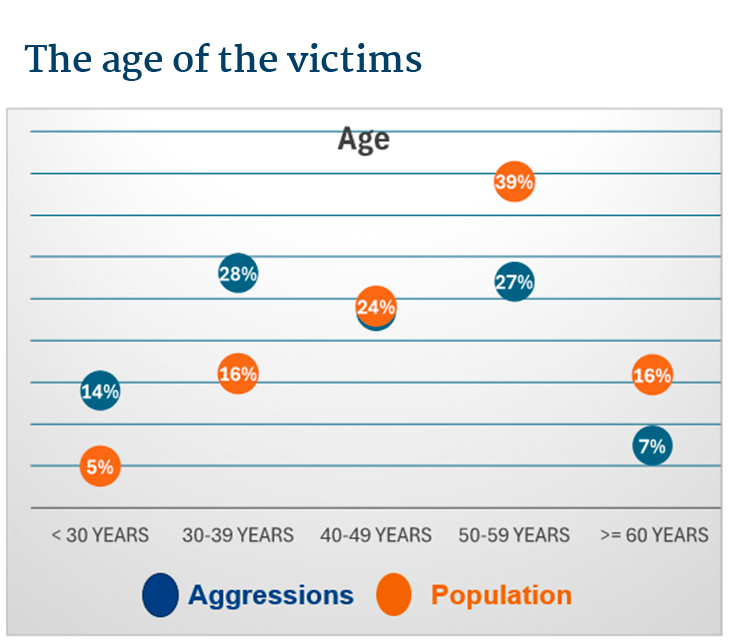

Regardless of the absolute number, it is possible to profile the most exposed categories, those overrepresented among the victims compared to their share of healthcare workers. Typically, young nurses (see image) are more affected than other healthcare staff. According to official data, women appear to be the primary targets of violence (ranging from verbal to physical). Adjusting the data for the total number of employees, though, 2% of employed women and 3% of men are affected each year, considering only official figures.

Of the total percentage of aggressors, 69% are the patients themselves, 28% are their relatives, and 3% are strangers. It should be noted that the aggressors are predominantly male. Regarding the profile of the aggressor, they are often people with social distress, mental alteration due to substances, emotional stress from the loss or critical condition of a loved one, agitation, or anger. They are often lonely individuals, who have shown signs of aggression before, accustomed to the codes of violence, even without specific premeditation. Thus, they are not often unknown to the operators and the service network.

Today, attacks on healthcare workers are in the rising phase of the attention cycle, and news reports on them are accordingly widespread. Episodes are almost always described as outbursts of anger against innocent victims, and the natural reaction is to ensure greater security. The main approach seems to be increasing regulations to counter the phenomenon. Italian Law 113/2020 introduced new aggravating circumstances and increased penalties for serious and severe injuries and sanctions for anyone engaging in violent conduct. It introduced ex officio proceedings, forced healthcare organizations to become civil parties, and made healthcare staff public officials in the performance of their duties, with the dual consequence of harsher penalties for attackers and greater obligations for the healthcare staff themselves.

Can the phenomenon be governed by the increase in regulations and the proliferation of signs referring to them?

The issue of insecurity and lack of trust is a characteristic of our time and is apparent in every aspect of people's lives. According to the 52nd CENSIS Report, “63.6% of Italians believe that no one defends their interests and identity, so they must take care of it themselves. Among those with a low level of education, the percentage rises to 72%; among those with low incomes it is 71.3%.” This is true for patients but also healthcare professionals. If we add issues related to job dissatisfaction and heavy shifts, the places where healthcare services are provided can become powder kegs, ready to explode. Often poor communication does not allow the patients to understand the experience they are having and to navigate a chain of services whose operation is not so immediate. The triggers of aggression are, in fact, multiple, and multiple must be the perspectives of its management:

Healthcare organizations can and must intervene first and foremost by safeguarding the mental as well as physical well-being of their staff. From our review of 750 scientific publications on the topic, we have identified a series of possible interventions to address the three components of the risk of violence against healthcare workers: the likelihood of occurrence; severity; detectability.

Detectability is ultimately a matter of safety culture. If its importance is shared and the staff trusts that reports will be followed by corrective actions, the phenomenon of underreporting is destined to decrease.

The likelihood of occurrence is mainly reduced by activities aimed at increasing staff well-being. A better state of mind, the existence of decompression spaces, and adequate training can develop a de-escalation capacity that can defuse many potential conflicts between healthcare workers and patients.

Severity, finally, should be mitigated by ex-post therapeutic interventions, which must be made available to the staff.

Thus, in complex systems like healthcare organizations, it is necessary to align strategic direction goals with those of the main macro-areas (departments, socio-health districts, etc.) to co-construct interventions that support healthcare professionals.

Moreover, communication with users should evolve from the concept of Public Relations Office, because those who experience discomfort in healthcare settings will not fill out the office's form but will express their anger in less civil ways.