- Start date

- Duration

- Format

- Language

- 2 Dic 2025

- 4,5 days

- Class

- Italian

“CompLab” is the blog on competitiveness and growth coordinated by Carlo Altomonte

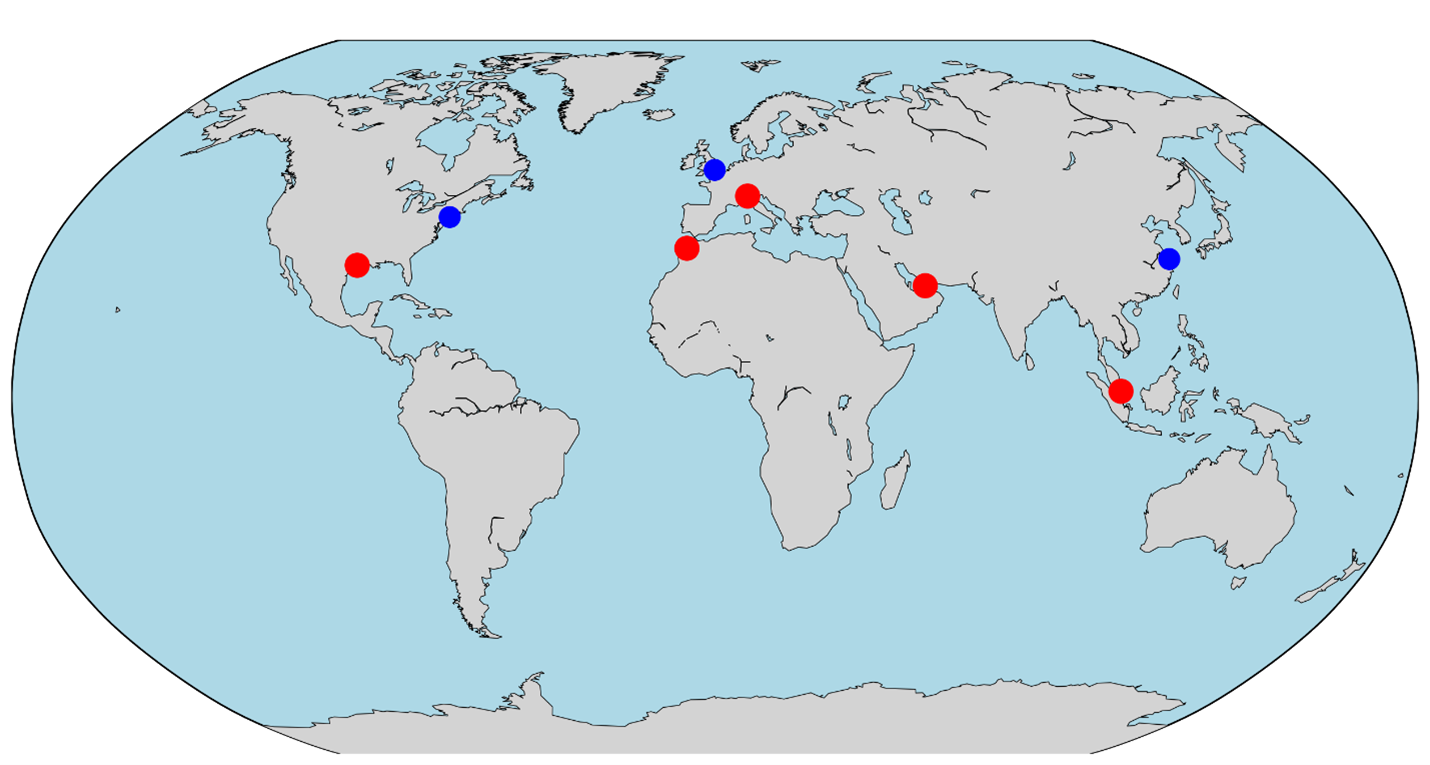

Over the past three decades, the map of globalization has been dominated by three main hubs: New York, London, and, increasingly, Shanghai, which has replaced Tokyo. These are the competitive poles of an ideal map of globalization — cities that have represented the pillars of the international economic system and the key nodes of the Global Value Chains (GVCs).

The logic behind this identification is straightforward. According to network theory, in a network where all nodes have equal probability of interaction — meaning that flows of trade, capital, or information can potentially connect any point — those that are geographically and functionally more central tend to display higher connection density.

In other words, position matters: those “at the center” of the network have more opportunities for exchange, more interactions, and more control over overall flows. Applied to the geography of the global economy, this theory explains well why New York, London, and Shanghai have emerged as dominant hubs. These metropolises are not only located at the vertices of the three macro-regions that have taken shape with globalization (North America, Europe, East Asia), but they also enjoy a topologically privileged position:

“Centrality” is therefore not only geographical but also functional: these cities concentrate infrastructure, institutions, and human capital that ensure what, in network terms, is called high betweenness centrality — that is, how often a node lies on the shortest path connecting any two other nodes, or its ability to mediate global flows. Without them, the paths of international finance, knowledge, and trade would become longer, costlier, and less predictable.

In recent years, however, the world network has lost some of its homogeneity. The probability of interaction among nodes — the ease with which capital, goods, people, and data move — is no longer uniform. Geopolitical tensions, trade wars, technological barriers, and sanctions have created more regionalized “sub-networks,” denser within themselves (as global trade in absolute terms has not declined) but more weakly connected to one another (trade among large blocs has diminished).

Returning to network theory, when a network fragments, the nodes that become central are no longer those at the center of the global system, but those located on the boundaries between two (or more) highly integrated internal networks. In other words, new centrality emerges at the margins — at the contact points where connections can still pass through. These are the bridging nodes — boundary nodes that link partially disconnected areas.

Looking at today’s global map, which cities embody these characteristics? The selection relies on a few structural indicators: capital attractiveness, ability to retain talent, demographic growth, and a role as an interface between regions. Based on these indicators, the cities emerging as competitive hubs in the new globalization could be:

Closer to home, we can think of Casablanca, now Africa’s financial gateway to Europe, where the number of international firms registered in the Casablanca Finance City has increased by +40% since 2021 (CFC Authority, 2024). And of course Milan, which combines advanced manufacturing and financial services, playing the role of “bridge” between Europe’s industrial North and the Mediterranean, with a +22% rise in foreign direct investment in the Lombardy region between 2021 and 2024 (EY Attractiveness Survey).

In network theory terms, all these cities exhibit potentially high edge betweenness: they manage the few but crucial links that still connect the major regional networks. Their strength lies not in internal density but in their ability to mediate — to turn fragmentation into opportunity.

To maintain this role as bridging nodes, in a world where the global network is no longer homogeneous and competitiveness is shifting from the center to the boundaries, another resource is required: knowledge. In today’s economy, the areas that thrive are not only those that connect capital, technologies, and goods, but also those that generate and transmit knowledge in original and creative ways. In the age of AI, the stock, attraction, and creation of human capital consolidate the role of cognitive hub — a new form of centrality and competitiveness.

Indeed, this seems to be confirmed by Singapore and Dubai, and by the growing production of knowledge they have achieved in recent years through the development and attraction of academic institutions and centers of research excellence. But let us not forget Milan, which still has strong cards to play in this game.

The new globalization will therefore not have a few dominant nodes at the center, but many intelligent nodes at the margins. And in this new geography of value, the winners will be those places that can turn their boundary position into a platform for knowledge and cooperation.