For an agriculture that regenerates both soil and the economy

“The dragonfly” is a blog on nature and business, coordinated by Sylvie Goulard

“You are dust, and to dust you shall return.” In Genesis (3:18–19), it is at the moment when Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit and are banished from the earthly Paradise that God mentions both Adam’s obligation to cultivate the soil to earn his bread and his ultimate return to the clay from which he was made. The nurturing earth embraces the entire cycle of life.

Too often, we have lost our connection with nature. While Indigenous peoples continue to call it Mother Earth, in the cities of developed countries we tend to forget the many services it provides. Yet it is the earth that gives us food and the fibers needed for the textile industry. It is the earth that inspires artists and offers city dwellers renewal and peace. It is the earth that helps us fight climate change by absorbing the carbon we emit. Soils, oceans, and trees all contribute to regulating temperatures, while vegetation helps combat erosion and drought.

These fragile balances are under threat. Forests weakened by heat and soils exhausted by overuse can no longer absorb as much carbon as when they are healthy. If we wish to preserve our environment—if only to continue benefiting from its resources—it is time to rethink our modes of production and consumption. This is not only an ecological or public health issue; it is above all an economic one. Companies have a vested interest in doing so: to safeguard their value chains, to better face physical, financial, and reputational risks, and ultimately to ensure their continued existence.

Since the Industrial Revolution—and even more so in the last century—our economic model has forgotten the circularity of life. We draw resources from nature far beyond what it can replenish. In our consumption, we often waste—for example, one third of all food produced is lost between the farm and the plate. We repair things less and less, we throw away objects and packaging, creating mountains of waste. As a result, plastic accumulates on beaches, in oceans, and even within our bodies. The cycle of life is no longer respected.

Another model is possible—one in which, as in nature, everything is connected and nothing is lost: a regenerative model that alone can ensure sustainable prospects. This is one of the themes explored in the study recently published by SDA Bocconi and a network of French companies active worldwide, entitled 2050Now Lamaison

How can we define regenerative agriculture? The study notes that, for now, there is no regulatory definition nor a single, unified vision. Andrea Illy, President of Illy Caffè, created the Regenerative Society Foundation to “systemically address the complex, interacting systems of environment, climate, society, nutrition, health, and lifestyle,” and proposes this definition of regeneration: “the set of processes aimed at keeping living systems healthy through the preservation, renewal, and restoration of natural assets.” Applied to all living organisms in an ecosystem—from microorganisms to humans—regeneration is based on the “four Rs” of a complete circular economy cycle: reduce, reuse, recycle, regenerate.

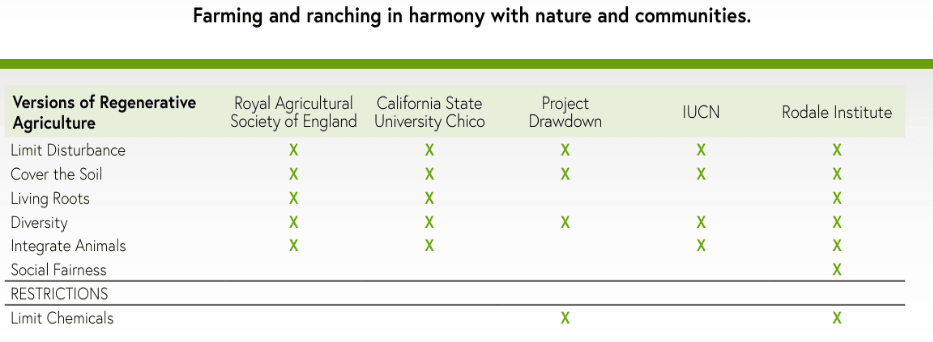

A June 2024 study by the Rockefeller Foundation, Financing for Regenerative Agriculture, attempts to summarize the distinguishing criteria that have emerged around the world. In most cases they overlap, though they are not identical: some include social equity, while others require limits on chemical inputs.

French researcher Philippe Grandcolas (CNRS) describes regenerative agriculture as “agricultural practices with fewer negative externalities, using fewer inputs, being more respectful of landscape diversity, and integrating biodiversity.” Warning against the proliferation of non-standardized labels and references (for example, in France, Haute Qualité Environnementale), he urges that practices presented as regenerative should include organic standards—particularly banning the use of pesticides, monitoring inputs, and assessing ecosystem conversion. For this reason, he prefers the scientific term “agroecology” over “regenerative agriculture.”

It is noteworthy that a luxury group such as LVMH has also taken an interest in the subject. The challenge is to ensure continued production in a context where intensive farming leads to soil depletion, pesticide overuse, and the decline of pollinators—a model that, quite literally, is not sustainable.

For LVMH, “Regenerative agriculture is defined as agriculture capable of restoring soil health and ecosystem functions (biodiversity, water cycles) while ensuring socio-economic stability for stakeholders (farmers, communities) and the production of high-quality raw materials.” To secure its essential supplies, the group has begun implementing regenerative agricultural practices for the production of grapes for Champagne and other spirits; cotton, wool, and leather for fashion and leather goods; and palm, beet, and iconic ingredients for perfumes and cosmetics.

The effort toward regeneration is not limited to agriculture. In forestry, new practices are emerging—for example, abandoning clear-cutting, where entire plots are felled at once by heavy machinery that damages the soil. Using lighter vehicles or even draft horses, adopting continuous-cover forestry, keeping dead trees in place, and preserving ponds and wetlands are all ways to allow forests to regenerate and remain healthy. They can then better fulfill their role as carbon sinks while producing higher-quality timber.

As for the oceans, simply ending overfishing, particularly trawling, has a positive effect on the renewal of marine resources.

When one thinks about it, these good practices are, at their core, a matter of common sense. Perhaps we must relearn them—while modernizing them, since technology can also play a role in today’s regenerative models. Recognizing ourselves as an integral part of nature and being aware of our fragility are essential if we are to fully reconnect with life and look ahead to future generations.